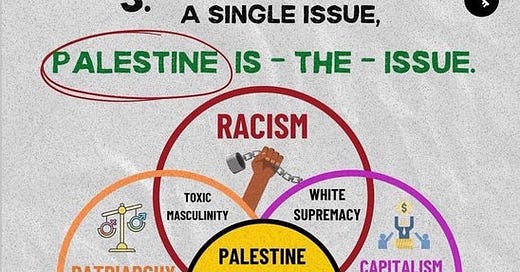

This week, the following graphic circulated on social media.

This is your brain on Manichaeism.

What?

Manichaeism was an ancient religion which taught that the universe is characterised by a conflict between God and the Devil. The elements of good and bad that we see in the world around us are manifestations of this deeper cosmic opposition. Manichaeism is long extinct as a religious movement, but the term has come to be used more generally to describe black-and-white worldviews in which the confusing and seemingly random course of human events is explained in terms of a metaphysical battle between forces of Good and Evil.

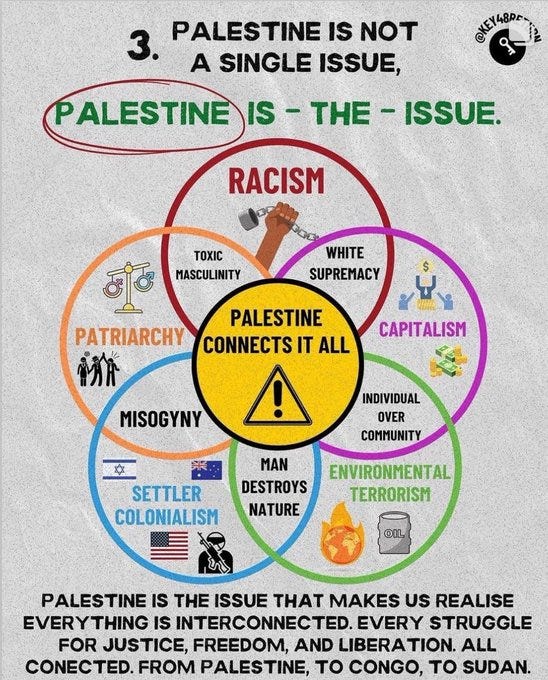

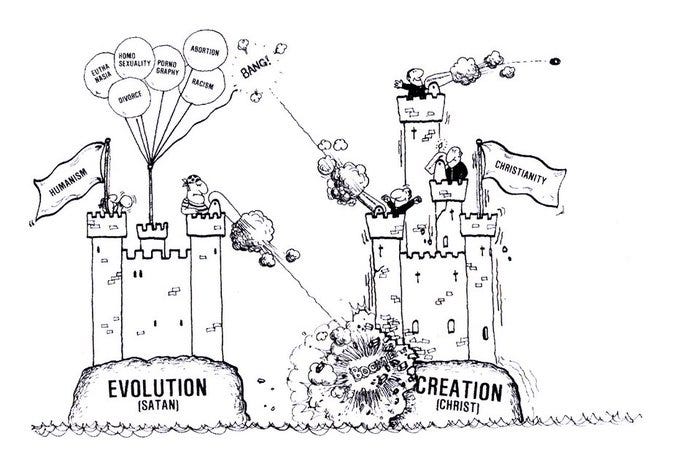

Orthodox Christians see Manichaeism as a heresy - God is the sole supreme being, and Satan is a mere rebellious creature - but Christianity is fundamentally indebted to the same way of thinking. Christian doctrine is strongly dualistic: good and evil, salvation and damnation, heaven and hell. Hence there exist right-wing Christian equivalents of the graphic above, like this one:

When you take Christian theology out of the picture - when Western society becomes secular or religiously indifferent - the crucial fact is that the same Manichaean framework remains popular. Its binary simplicity has a timeless appeal to the human mind. Indeed, that is an important reason why absolutist religions like Christianity gain a following in the first place.

I am going to make the case that graphics like the one at the top of this article do not amount to rational advocacy for the Palestinian cause. They are not an example of ‘normal’ political criticism of Israel (or Zionism, or Netanyahu, or the Gaza war) - which can, obviously, be put forward perfectly legitimately. They are an example of radical and irrational Manichaean ideas which connect with an old tradition of antisemitism. The notion that Zionists are the root of all the evils in the world did not suddenly spring into life last week on social media. It has a long and ignoble history in Western thought.

*

The story begins in the unfamiliar world of eighteenth-century Europe and the aftermath of the French Revolution of 1789. Pre-modern Europeans lived in a thought-world which is alien to us today. The traditional royal and religious order was regarded as the creation of God himself. Liberalism and democracy could not be taken seriously as legitimate alternatives; any dissent against the Throne and the Altar amounted to rebellion against the ruler of the universe. In this black-and-white Manichaean mindset, the French Revolution was a profoundly evil event: in the words of the leading reactionary philosopher, Joseph de Maistre, it was “Satanic in its essence”.

Christian royalists asked themselves how something so wicked had happened. After all, King Louis XVI was a nice man. The people loved their landlords and their priests. The guilty party was ultimately Satan, of course, but he needed to work through human agents. Who were these? Conservative intellectuals arrived at the seemingly bizarre answer that they were Freemasons.

One of the most remarkable developments of eighteenth-century European culture was the spread of private fraternal societies – and the Freemasons were the best known of these. Freemasonry evolved in Scotland at the end of the 1500s out of working stonemasons’ guilds; it migrated to England, and by 1789 it had spread extensively in continental Europe. As a fraternal order, it was characterised by a peculiarly male mixture of brotherhood, fantasy, ritual and hierarchy: a kind of Star Wars cosplay for grown-ups.

For the most part, Freemasons and members of other fraternal orders were bored rich men who were looking for entertainment and networking opportunities (much like today). Many of them had conventional religious views and no great interest in fomenting political change. Indeed, some of them seem to have seen their movement as a bulwark of conservatism. Pope Clement XII condemned Freemasonry in 1738, but he was widely ignored. There was no real concerted effort on the part of Europe’s ruling classes to put down fraternal societies – unsurprisingly, since not a few of them happened to be members of them.

Some of the brethren, however, had more radical perspectives. Some Masons were interested in occult ideas. In France, for example, there developed an esoteric sect known as the Martinists. Others were political radicals. These included a group in Bavaria called the Illuminati, which was founded by a self-important fool called Adam Weishaupt. Weishaupt planned that his organisation would undermine royalism, aristocracy and Christianity by gradually winning over influential men. The Illuminati got nowhere: they were banned and their activities were publicly exposed in 1784-87. Yet the resulting scandal gave some plausibility to the idea that the established order was threatened by conspiratorial societies.

In any event, within a couple of years of the French Revolution, conservatives were blaming it on a conspiracy of Freemasons who were doing the work of Satan in a cosmic battle against God Almighty. The rotten fruits of modernity - liberalism, secularity, the capitalist market economy, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, electoral democracy - were lumped together as the products of this conspiracy. This was the right-wing equivalent of the graphic at the head of this article. It should go without saying that it was nonsense. Freemasonry was in decline in France in the years leading up to 1789; and it has been estimated that a quarter of French Masons on the eve of the Revolution were themselves Catholic clerics. The Revolution led to a fall in Masonic activity because the radical revolutionaries saw it as too aristocratic. At most, we might say that the Masonic movement offered reformers opportunities for networking and organising, and that it had a general influence in spreading Enlightenment values. But it did not bring about the Revolution as an organised force, and no-one today seriously argues that it did.

The main promoter of the Masonic conspiracy theory was a Frenchman, Fr Augustin Barruel. Barruel was a genuine religious fanatic, the patron saint of unhinged conspiracy fantasists. His masterpiece, Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism, provided a detailed history of three supposedly interlocking conspiracies, the ‘Antichristian conspiracy’, the ‘Antimonarchic conspiracy’ and – worst of the lot – the ‘Antisocial conspiracy’, whose members believed in anarchism, atheism and communism. In some ways, Barruel’s book is a monument of research and detail. But he had the classic vices of the conspiracy theorist: he exaggerated and he over-systematised. Everything had to be part of an overarching framework of Evil against Good. Everything had to be connected to everything else. Again, you see the relevance to the graphic that we began with. Unfortunately, not everyone saw through Barruel as the crank that he was. Some powerful people came to be converted to the Manichaean conspiracy theory, including Chancellor Metternich of Austria and Pope Pius VII.

The early decades of the nineteenth century saw the first attempts to insert Jews into the theory. Barruel and others had briefly mentioned the Jews in their work, but the original form of the theory was not really antisemitic. Nevertheless, from the 1780s and 90s, Jews across Europe had been emancipated from the strictures of several of Europe’s Christian monarchies (although not always permanently). Some weirdos asked, as they always do, cui bono? Perhaps the Jews were behind the revolutions. This thinking led to the first stirrings of what became known as Judaeo-Masonic conspiracism. In the so-called ‘Simonini Letter’ (1806), an Italian soldier wrote to Barruel asking him to make his theory more anti-Jewish. This was followed by a widely unread French pamphlet, Le Nouveau Judaïsme (1815) and a Portuguese tract, Maçonismo Desmascarado (1823). The British politician Benjamin Disraeli, whose relationship with his Jewish ethnicity was complicated, associated the Jews with revolutionary secret societies in Coningsby (1844) and Lord George Bentinck (1852). No-one knows what drove him to make his infamous claim that “the world is governed by very different personages from what is imagined by those who are not behind the scenes”. Perhaps it was a joke. But conspiracy theorists were listening and did not forget it.

While Disraeli was writing, another form of antisemitism was gestating. The old Christian belief in Jewish money-power was turning into a modern myth of Jews as oppressive capitalists. The founding figure of this tradition – the ‘socialism of fools’ – was the French intellectual Alphonse Toussenel, who published Les Juifs: rois de l’époque in 1845. Toussenel was no Barruel. He supported the idea of a social revolution, and he was not interested in Freemasons. But he argued that traditional structures of authority had protected working people; and that modern liberalism had withdrawn that protection, allowing rich Jews to exploit them. In 1846, another Frenchman, Mathieu Georges Dairnvaell, wrote a pamphlet entitled Histoire édifiante et curieuse de Rothschild Ier, Roi des Juifs, using the pen-name ‘Satan’. He claimed that Nathan Mayer Rothschild had made an enormous profit from advance knowledge of the outcome of the Battle of Waterloo. This claim turned into a broader myth about the Rothschilds being warmongers.

*

The Judaeo-Masonic conspiracy myth took shape in its classic form in and around the 1860s, in a series of writings from different countries across Europe. There was, for instance, Hermann Goedsche’s novel Biarritz (1868), which became a source of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. There was August Rohling, who repeated some old libels about the Talmud in Der Talmudjude (1871). Most remarkably, there was Roger Gougenot des Mousseaux, a right-wing aristocrat and writer on religious subjects, who published a bizarre book entitled Le juif in 1869. Gougenot had a particular interest in the occult, a subject on which he had already written several works. He was of the opinion that magic was the key feature of the revolutionary secret societies, and that the Jews were occultists par excellence. He had a chip on his shoulder about the Jewish mystical tradition known as the Kabbalah. The Kabbalistic tradition (he told his readers) could be traced back to the descendants of Cain, the first murderer and the first human to be cursed by God. It had been mixed with pagan Greek and Indian ideas; and it was inextricably linked with magic and sorcery.

Such ideas were not confined to a fringe of demon-haunted bigots. They were endorsed by the supreme leadership of the Roman Catholic Church. In the 1865-66 edition of the official journal of the Vatican, the Acta Sanctae Sedis, we find a decree of the Inquisition with a rather strange commentary attached. The decree was issued in response to an inquiry from a group of American bishops who were faced with the question of how to address the growth of the Irish nationalist movement known as the Fenians. The Vatican’s line was that the Fenians belonged to the same category of subversive secret societies as the Freemasons and their like. They were instruments of Satan. They not only taught atheism, pantheism and socialism, but also demonic occultism:

....[U]ltimately, you will be unable to deny that the supreme architect [a Masonic phrase] of these societies... is none other than he who in Sacred Scripture is called the prince of this world.... It should therefore be no surprise that, in societies of this kind, there is rather considerable evidence of demons making their presence known. Such phenomena used to be called magic, theurgy, sorcery, negromancy, magical ecstasies, etc. Today, they take a different form, and they are referred to as Spiritualism, or indeed the miraculous effects of animal magnetism.

It may have come as a surprise to Irish nationalists that they, like the Masons, were trafficking with demons by means of Spiritualism, but there we are.

On and on the madness went. The best known conspiracist of the century was Édouard Drumont, who veered between being Catholic and anti-Catholic but was consistent in what he thought about the Jews. In La France juive (1886), he introduced a new wave of readers to the theory of a centuries-old plot of Jews and Freemasons. Meanwhile, the Jesuit journal, La Civiltà Cattolica, which was published with Vatican approval, waged a years-long antisemitic campaign. And the fledgling Zionist movement began to enter into the polemic. In 1882, Fr Emmanuel Chabauty made the ludicrous claim in Les juifs, nos maitres! that Russian Jews were invading Romania in order to create a “provisional kingdom” before returning to Zion. They were supposedly fleeing Russian terrorism: but Chabauty explained that this consisted of false-flag attacks carried out on Jewish orders by Russian nihilists, who were a branch of Freemasonry. Monsignor Augustin Lemann, a converted Jew who was an expert on the Antichrist, suggested in L’antéchrist (1905) that Zionism could be a means of preparing the way for the Antichrist to have his capital in Jerusalem (he also believed that the famous formula 666 might have something to do with the Freemasons). The most intellectually hefty conspiracist of his day, Monsignor Henri Delassus, wrote in La conjuration antichrétienne (1910) that the return to Zion would mean a Jewish world government. He also played the Devil card. He believed that Judaeo-Masonry was literally Satanic. The French Revolution, like the Reformation before it, had been preceded by a rise in occultism; Satan was working to make the secret societies his own, while driving the mass of the people to atheism; and Spiritualism was part of the scam.

In the secular world, Manichaean antisemitism was also reaching a climax. The liberal journalist and intellectual J. A. Hobson claimed in The War in South Africa (1900) that the Second Boer War was the product of a Jewish conspiracy. In 1902, he published a more influential book, Imperialism, which was famously republished in 2011 with a commendatory foreword by the Right Honourable Jeremy Corbyn. In this latter book, Hobson largely reined in the overt antisemitism, but he could not help making dark references to the Rothschilds and to “men of a single and peculiar race, who have behind them many centuries of financial experience”. He didn’t mean the Bantu. Such ideas were not personal eccentricities of Hobson’s. Others on the British political left also saw Jews behind the Boer Wars. The leader of the Social Democratic Federation, a Marxist group, wrote an article entitled ‘Imperialist Judaism in Africa’ in 1896 in which he stated:

We say it is high time that those who do not think that Belt, Barnato, Oppenheim, Rothschild & Co. ought to control the destinies of Englishmen at home, and of the Empire abroad, should come together and speak their mind..... Let us not forget... that this buccaneering and bloodshed is part of a great project for the constitution of an Anglo-Hebraic Empire in Africa, stretching from Egypt to Cape Colony and from Beira to Sierra Leone.... [L]et us with one accord declare against this shameful attempt of a sordid capitalism to drag us into a policy of conquest in tropical regions which can benefit no living Englishman in the long run, though it may swell the overgrown fortunes of the meanest creatures on the earth.

This drivelling by Victorian and Edwardian Brits over long-finished wars should be of little interest today, were it not for the fact that people still insist on seeing invisible connections between Jews, imperialism, capitalism and all the rest of it. As it happens, Hobson in particular got some important people to listen to him. One of these was Vladimir Lenin, who was influenced by the Englishman’s work in his own Imperialism (1917).

At this point, we cannot avoid mentioning the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. So much has been written about this sad and demented text that there is little to add. The Protocols were plagiarised from several pieces of nineteenth-century political literature, and they were probably written in Russia in 1901-03. They may have been written as a direct response to - indeed, as a parody of - the founding text of Zionism, Theodor Herzl’s Der Judenstaat (1896). They certainly came to be presented as the minutes of secret meetings held at the First Zionist Congress of 1897. The Zionists were secretly plotting to bring about everything bad in the world, from socialism to capitalism and from mass education to constitutional government. Defeating them would pave the way for a universal restoration of the right order of things. This sounds familiar, but one thing was still missing at this point - no-one gave a damn about the Palestinians. That part of the story only came later, after World War I.

*

The Manichaean myth of the Judaeo-Masonic conspiracy was the creation of European Christians. It had no real roots in the Islamic world (although it made brief appearances there before World War I: the Young Turks and the Persian Constitutional Revolutionaries were accused by their opponents of being Jews or Freemasons). The myth really only came to the Middle East in the period after the Russian Revolution, as the Protocols were carried outside Russia and promoted as offering an accurate explanation for what had happened there. The Protocols were translated into Arabic in the 1920s; and from the 1930s they were reinforced by Nazi radio propaganda broadcasts in Arabic and Farsi. These broadcasts presented Jews, Zionism and the World War II Allies as the enemies of Islam and ultimately of the whole world. These themes survived the defeat of the Nazis and lived on into the 1950s in the independent Arab and Muslim states. They were embraced by figures as different as King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, Ayatollah Khomeini, Gamal Abdel Nasser, and Nasser’s sworn Islamist enemy Sayyid Qutb.

In Soviet Russia, the Protocols were banned, but the underlying Judaeo-Masonic theory prospered in a different guise. In the years after World War II, antisemitic and antizionist ideas were increasingly embraced by the communist regime, from Stalin down to professional ‘Yidologists’. This process accelerated in the period after the Six Day War of 1967. Antisemitism shaded into antizionism without meaningful distinction, and Tsarist material from the milieu of the Protocols was recycled with a tactical search-and-replace of ‘Zionists’ for ‘Jews’.

By the 1970s, Soviet antizionist propaganda broadcasts to the Middle East were reinforcing the existing Manichaean narratives that had existed there since before World War II. Western foreign policy, they claimed, was not a banal matter of states pursuing their material interests, as states always do. It was an imperialist conspiracy for world domination by capital in which Jews or Zionists – again, there was no meaningful difference between the two categories – featured prominently. It is against this background that we should understand the notorious fact that the original 1988 Hamas charter endorsed the Protocols and claimed that sinister secret societies like the Rotary Club were behind the French and Russian Revolutions.

These strands of thought - from Arab nationalism, Islamism and Soviet propaganda - infected the Western extreme left in the 1970s. This is the tradition that radical antizionists are drawing on today when they argue that Palestine is a queer issue, a reproductive rights issue, a climate justice issue, and so on. It is Manichaean fantasy posing as political analysis. It actively undermines rational criticism of Israeli state policy from a humanitarian or international law perspective. The kind of extravagant, demonising polemic against Israel and ‘Zionists’ that we began this article with is the product of a wholly different discourse: it is the end-point of a discreditable tradition that started with baffled French Catholic royalists in the 1790s. It is this tradition that can be heard to speak when Israel is presented as the controlling force of American and therefore global policy; when people refer to Keir Starmer as ‘Tel Aviv Keith’; when Western media is seen as being corrupted by Zionist influence; when the ‘hand of Israel’ is seen wherever bad things happen; and when a conflict between rival nationalisms over a piece of land smaller than Belgium is framed as the central moral issue of the age and the key to the destiny of the world.

It’s not just me, by the way. Others have made similar points before. Jean-Paul Sartre, whose relationship with Zionism was not straightforward, perceptively saw the origin of antisemitism as lying in Manichaean dualistic thinking:

Anti-Semitism is thus seen to be at bottom a form of Manichaeism. It explains the course of the world by the struggle of the principle of Good with the principle of Evil.... The reader understands that the anti-Semite does not have recourse to Manichaeism as a secondary principle of explanation. It is the original choice he makes of Manichaeism which explains and conditions anti-Semitism.

It should also come as no surprise that there is empirical evidence that a Manichaean worldview is a good predictor of conspiracy beliefs. This is a style of thought that belongs with Barruel and his successors: a worldview populated by demons and Antichrists, even if they are no longer acknowledged as such. It is a style of thought which has no room for the mundane processes and compromises of liberal democratic politics, and which readily descends into hostility and contempt for elections and laws. The visual rhetoric of the graphic that we began with implies that the whole existing order of the world is corrupt. Everything is stitched up by the powerful. The system is not there to be participated in but to be smashed.

This way of thinking is anti-democratic, anti-liberal and, in a real sense, anti-political. History is a drama – a morality play – which is played out by actors who are in the service of God and Satan, or of the ideological abstractions that serve as their secular equivalents. Because things that happen in the human world involve individual actors rather than impersonal forces, the agents of evil are given faces; and those faces are dreadfully familiar. Even if they no longer believe in devils, Manichaean radicals certainly do believe that Israel is to be equated with abstract evil absolutes - racism, patriarchy, capitalism, etc. - in a polemic which loses any meaningful contact with the real offences of Netanyahu and his Kahanist friends. They are magical thinkers; and even if they no longer believe in literal magic, they do believe that the Jewish state has a kind of metaphysical strength and power in the world. Conversely, to defeat Israel is to unlock the door to a general victory of the cosmically good side. Such a style of thought was certainly very much at home among 1790s Catholic royalists. It would have been better if it had stayed there.

not a subject I knew anything about. Thanks for the insightful introduction!